Biosecurity encompasses a range of measures designed to prevent the introduction and spread of diseases to protect herds, ensuring the profitability of individual operations and the sustainability of the industry. However, despite our best efforts, a biosecurity gap can emerge, presenting notable challenges and potentially undermining the core of the pork industry. Bridging the biosecurity gap requires a comprehensive approach that includes vigilance, industry collaboration, ongoing training, and continuous adaptation as we learn more. Dr Susan Rodakis, technical manager for pigs and poultry at Zoetis, explored where gaps in biosecurity can happen and ways of bridging the biosecurity gap.

What is biosecurity, anyway?

She said there is no single definition for biosecurity: “The World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) defines it as a set of management and physical measures designed to reduce the risk of introduction, establishment, and spread of animal diseases, infections or infestations to, from, and within an animal population”, while the United States Association of State Departments of Agriculture looks at biosecurity in terms of protecting the health of humans, animals, and the environment from biological threats (Renault et al., 2022). Additionally, different views – like the inclusion or exclusion of humans in the definition – makes it difficult to agree on the steps needed to implement various biosecurity measures.

“If we cannot agree on a definition, there will be gaps!”

At the same time, the principles of biosecurity are rapidly changing. Today’s world is different to that of the 1960s when large-scale, industrial farming first boomed. The rise of larger, specialised farms and changes in the way we trade bring with it different kinds of disease risk dynamics, according to Dr Rodakis.

For example, she said, “Research by Dee et al. (2021) suggests that select viral pathogens of pigs can survive in certain feed ingredients during real-world commercial transit. Data like this illustrates that we need to consider other materials, not just the ones we normally focus on, like feed or raw materials for feed as a risk for spreading disease.”

One biosecurity

One Health illustrates the interconnectedness of human health with that of animals and the environment. “If gaps are found between these areas or disciplines, these gaps could be where biosecurity can fail,” explained Dr Rodakis. She referred to an article by Hulme (2020) following the SARS COV-2 pandemic, where he proposed the concept of ‘One Biosecurity’. His proposition is to engage experts from very different fields to the ones that farmers would traditionally consult on biosecurity, for example, engineers, chemists, population biologists, geographers, and social scientists, to ‘provide a more holistic understanding’ which would lead to improved approaches to dealing ‘with threats that impact multiple sectors’. “More gaps in our knowledge will emerge as we learn more about biosecurity – this is normal.”

Do not confuse strategy with tactics

Dr Rodakis used the analogy of a business plan that may fail for numerous reasons; for example, if you have forgotten why you drew it up, if it is not being used, or if it has been drawn up in the boardroom and passed down with no explanation. The same goes for a business plan that might be too rigid or complex, or if there is no one on the ground with the authority to make changes as needed.

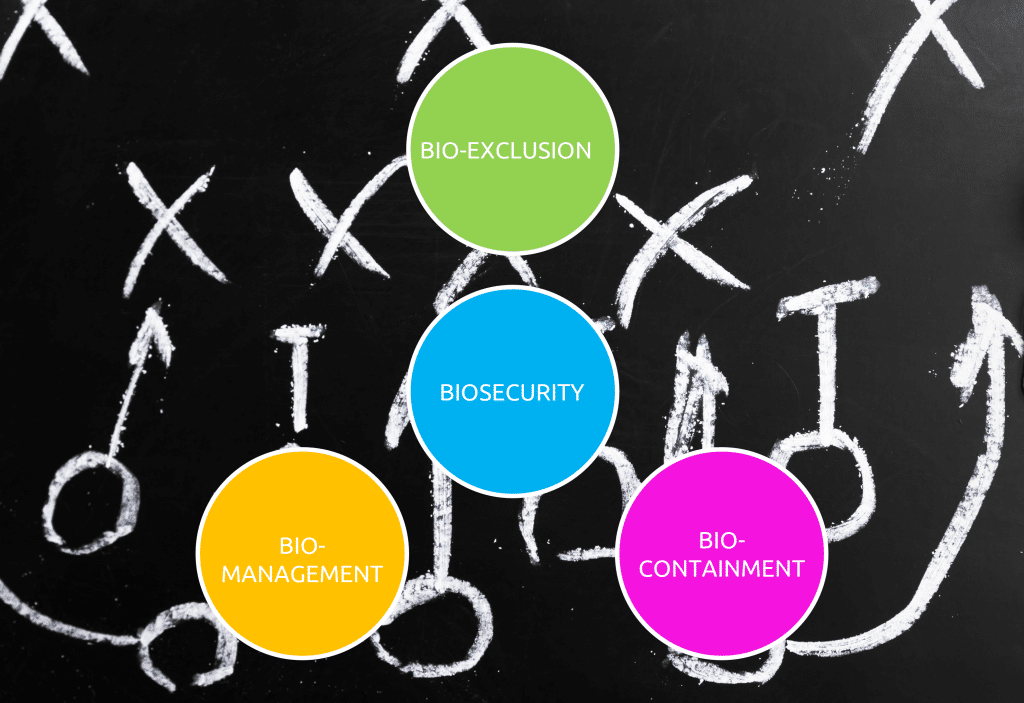

“Let’s apply this to biosecurity, which comprises three concepts: bio-exclusion, when diseases need to be kept out; bio-containment, the containment of a disease in one place to prevent it from spreading; and bio-management, when a disease needs to be managed on a farm.”

She advised farmers not to lose sight of the overall strategy (biosecurity) by only focusing on mastering specific tactics; for example, doing an excellent job of spraying the truck’s tyres, but ignoring that the truck is full of pig manure.

Implement the plan appropriately

Dr Rodakis emphasised that employees need to understand biosecurity measures to be able to implement them correctly. “If your farm’s biosecurity plan is not being used, ask why?” It can be because the team has not been involved.

“When drawing up a new biosecurity plan, involve as many stakeholders as possible. The employees who will carry it out will have insight into what will not work or if there’s an error in judgement.” Even if you cannot implement all the suggestions, it gives the team a chance to contribute which drives ownership of the plan.

She advised producers to consider how biosecurity training sessions are conducted and offered the following suggestions:

- Do biosecurity training during your annual training sessions, with additional short-term, high-impact sessions in between to keep the message fresh. Long training sessions might help with short-term revision, but, within a year, all might be forgotten.

- Allocate sufficient time to training. Revisit concepts at the end of the training session to ensure the key messages came across and check what has been retained.

- Consider who gives the training. It should be a trusted individual and reliable source of information with credibility, such as a veterinarian, so trainees are willing to learn.

- Keep the context in mind. If it is too complex it might be too challenging to follow. Distil complex biosecurity strategies into easy-to-follow steps. Each step should be simple to remember and implement.

- When training is done properly, and the trainees understand what is needed of them, and why, they take ownership of the plan, drive it, and hold each other accountable.

It is not a one-size-fits-all approach

“The same biosecurity plan cannot be copy-pasted between farms, it needs to be adapted.” She said the first consideration is economics, as it is costly implementing a strategy and keeping it running. “Start with the most important and impactful tactics first.”

Dr Rodakis emphasised that some of the biggest risks are introduced when people relax and become complacent; for example, if they know the source of their replacement gilts. “Bringing in gilts from a different part of your operation still carries biosecurity risks because you are introducing different animals into a new environment.”

She said producers should be cognisant of the gaps that may occur in day-to-day operations when exceptions are being made. “Every visitor must be treated equally and follow the same biosecurity principles that are implemented daily by the on-farm team.”

She concluded by saying, “Biosecurity will continue to be a relevant concern. Better understanding around why we are implementing it and well-thought-through plans that can be properly implemented can help lead to less gaps in biosecurity.”

This article will be published in the summer 2023 issue of PORCUS PrimeCuts.

The South African Pork Producers’ Organisation (SAPPO) coordinates industry interventions and collaboratively manages risks in the value chain to enable the sustainability and profitability of pork producers in South Africa.