Numerous factors may cause lameness in sows, from genetics and nutrition to housing conditions and herd health management. It is a multifaceted challenge that impacts animal welfare, compromises reproductive success, decreases farm performance, and reduces economic viability. Lameness requires targeted strategies to prevent and/or cure was the message from Tim Horne, area manager for Europe and South Africa at Zinpro Corporation.

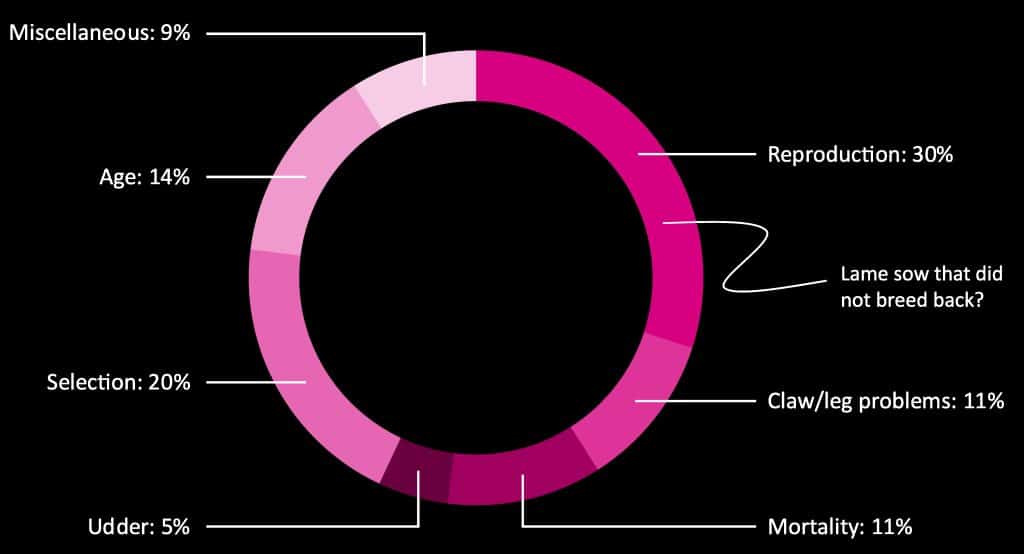

“Lameness in pigs is underestimated as it could be a subclinical problem that often goes unnoticed. The causes of culls are often also wrongly classified; being frequently misattributed to reproductive failure or classified as ‘miscellaneous’,” said Tim Horne. “While ‘reproductive failure’ may be the reason for their exit, the cause is subclinical lameness due to inflammation. Finally, preventing lameness should be an obligatory ethical and welfare issue that goes beyond profit and production.”

Risk factors for lameness

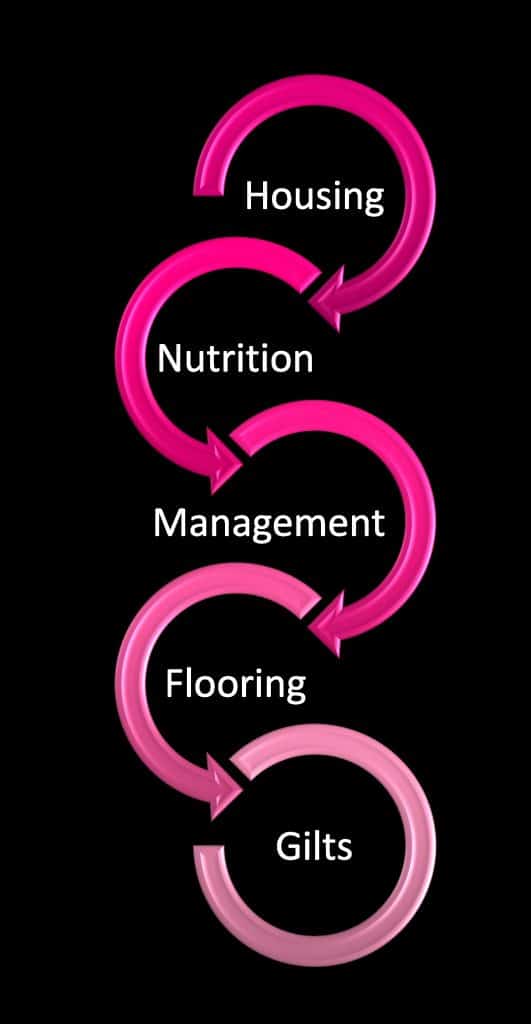

Horne said that a sow’s longevity increases productivity and decreases costs. “Certain physical challenges may predispose gilts and sows to lameness, such as older, poorer housing, slippery floors with bolts, and large gaps in slats.

Introducing gilts into the breeding herd may cause fighting during socialisation, especially if there is limited space. Poor mineral and vitamin nutrition could cause osteochondrosis (between about 16 and 20 weeks), which aggravates lameness.

An imbalance of calcium and phosphorus may also be a cause of pig lameness.”

The leading ‘hidden’ cause: Inflammation

Metabolic changes in pigs, including lactation and mastitis, constipation, leaky gut syndrome, the presence of antinutritional factors, heat stress, and detritus, result in higher inflammatory stress. This slows keratinocyte cell proliferation in hooves and causes lesions in the hoof structure, which predisposes it to damage and lameness.

According to Horne, inflammation is essential for survival as it protects the body by activating the body’s defence mechanism. However, chronic inflammation does more harm than good. “When a pig experiences severe heat stress, the blood is redirected to the animal’s periphery for cooling. The gut, the largest organ, experiences reduced blood supply, leading to weakened tight junctions and increased permeability.” He said this allows harmful endotoxins into the blood, which causes macrophages (defence cells) to release inflammatory mediators, such as Interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα). “This negatively affects keratinocytes (keratin-producing cells) in the pig, which slows reproduction and hoof development. Chronic inflammation further weakens the gut’s lining, exacerbating leaky gut syndrome.”

Under lower stress conditions, pigs exhibit a faster, more targeted immune response. This lower and less destructive inflammatory response does not interrupt hoof growth or hoof quality and lessens the predisposition to lameness, and this results in increased health and longevity.

Increasing sow longevity and reducing replacement rates

“At first glance, it may appear that the higher the breeding weight of a gilt at first service, the higher the number of piglets born. Fatter gilts seem to produce better retention rates in subsequent parities than leaner gilts. However, as a gilt’s weight increases beyond 150 kg to 160 kg of good back-fat thickness, there’s a dramatic drop in the number of piglets to get to the next parity. Big, lean gilts show the

poorest lifetime performance.”

Gilts often perform worse compared to sows in their first parity. “A high proportion of gilts in the herd decreases the overall performance of the herd. Pigs produced from gilts are smaller and lighter than those produced from sows. Piglets from gilts often also have a lower survivability rate. Over time, it’s essential to replace certain animals in your herd as performance drops in later parities and genetic improvement is critical. However, I suggest a maximum of 18% of gilts introduced per cycle, which translates to a replacement rate of between 40% and 45% annually. The target should be a minimum of between 85% and 90% of gilts reach parity three to ensure sow longevity.”

Horne noted that when replacing a sow with a gilt, investment was needed for it to reach the point of service. “On average, gilts produce three fewer pigs – one less born, two less surviving – and result in 54 kg less meat due to smaller piglets. That’s about R25 000 per sow. Consider this across your herd. With a replacement rate that is 1% too high, you’re looking at R255 per sow per year.” He said the bottom line is that better sow longevity will result in fewer gilt litters, increased herd birth weight, better quality piglets, and a higher weight and better health at weaning – meaning a larger and heavier herd overall.

“The cost of lameness goes beyond buying gilts, it’s also an ethical issue. Lameness is a production bottleneck that could cause reproductive issues. Reducing inflammatory responses reduces lameness,

improves herd health, and increases productivity, while bolstering profitability.”

This article will be published in the summer 2023 issue of PORCUS PrimeCuts.

The South African Pork Producers’ Organisation (SAPPO) coordinates industry interventions and collaboratively manages risks in the value chain to enable the sustainability and profitability of pork producers in South Africa.