The next agricultural revolution is underway. Technological advancements, rapid genetic improvements coupled with novel data capture all combine create more sustainable animal protein production systems. These systems will help circumnavigate disease outbreaks, tackle resource scarcity, and ultimately results in economic longevity for all industry stakeholders. Dr Craig Lewis, chair of the steering committee for the European Forum of Farm Animal Breeders, led the discussion on navigating a rapidly evolving world and the stark economic realities that are essential for exploring the path that will shape the future of the global and African pig industry.

Dr Lewis said that Africa’s exploding population positioned the continent’s pig industry to provide affordable animal protein while encouraging growth in new markets. “Technological advancements have enabled the extensive collection and analysis of data to ultimately result in faster genetic improvements.” By measuring lean growth rate, mortality, and animal behaviour, among other factors, farmers are able to perform better within their given environment. This data allows for the incorporation of more favourable, disease-resistant animals in future generations.”

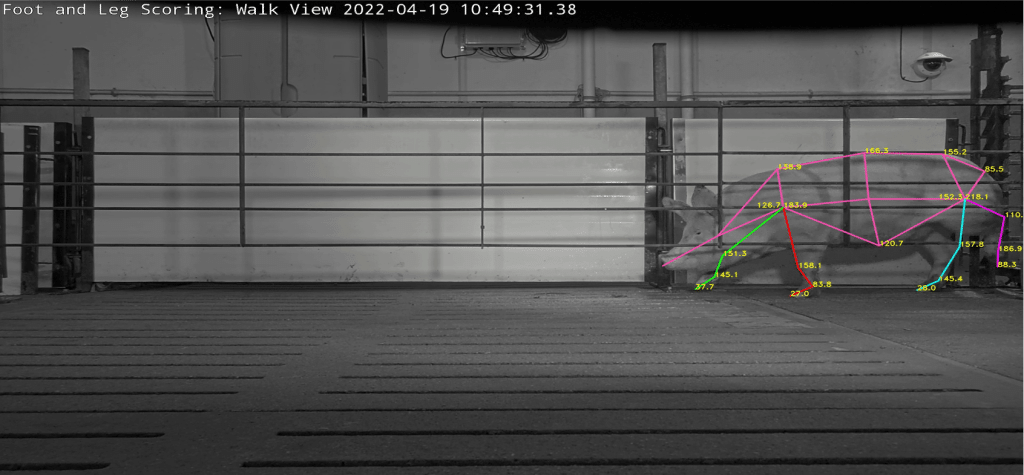

He mentioned that artificial intelligence was being used in nucleus and multiplier farms, impacting producers throughout Africa to take advantage of large-scale data in cross-bred situations for use in breeding programmes and for genetic improvements. “This allows scientists to untangle genotype-by-environment interactions, resulting in more robust animals (Image 1), more pigs per lifetime, and lower whole-herd feed conversions.”

Precision in breeding

Gene editing or genetic improvement involves targeting mutations that could naturally occur within each generation while selecting for the best possible outcome. It is not to be confused with a genetically modified organism, which introduces external genetics into an organism.

Dr Lewis commented that the best example of gene editing for genetic improvement is the pig that is resistant to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS). “By targeting and making small edits in the pig’s genome, the PRRS virus cannot enter the animal, resulting in true disease resistance. If pigs from South Africa, for example, were genetically resistant to African swine fever, it would transform the sector, affect production costs andoutputs, and impact global competitiveness and, potentially, trade agreements.”

However, he said, it is not merely about profits as healthy pigs experience better welfare. They are also less predisposed to infection by secondary diseases, which reduces antibiotic use. “Healthier, more efficient pigs use resources more efficiently, decreasing their carbon footprint per kilogram of meat sold. In the future, farmers may be able to sell livestock and carbon credits if they emit fewer emissions to begin with. Agricultural carbon efficiencies may also become a measure to secure funding.”

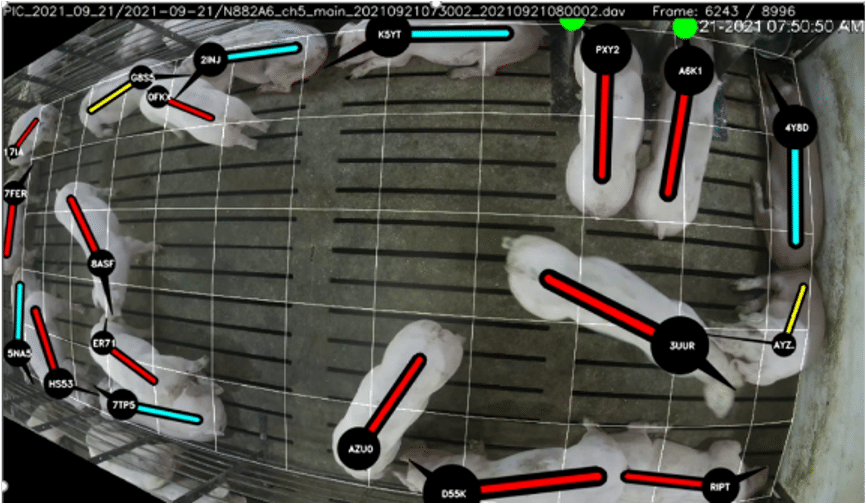

Another key area for future research is animal behaviour. “In terms of animal behaviour, one veterinarian may perceive a pig as aggressive, while another might say it’s inquisitive. While opinions are subjective, new technology measures and analyses individual animals’ interactions with humans and each other (Image 2). Selecting for positive behaviour, like docile pigs (a heritable trait), drives efficiencies and delivers pigs to farmers that are easier to manage, especially in the face of ongoing labour issues.”

Access to the best

Dr Lewis reiterated that the collective dissemination of genetic improvements, coupled with pre-competitive collaboration, has the potential to level the playing field. “Gene editing has potentially greater applications for farmers in the developing world than in Europe.

This offers Africa the chance to lead in their deployment. Starting today, a key message is to take advantage of all of the new technologies, even before gene editing is deployed, and optimise genetic flow. The farmers in Africa can do so by effectively importing frozen semen, driving replacement rates, and selecting optimal animals for breeding.

Once gene flows are efficient, then new technologies can be deployed more effectively. Indeed, “Gene editing is only one new technology that can impact genetic dissemination. Embryo transfer of sexed semen could also impact the transfer of genes from all over the globe to African producers, resulting in more high merit pigs to help promote food security, while simultaneously improving animal health and welfare. It wouldn’t have to be a choice between one or the other. New technologies enable us to have our cake and eat it too.”

External factors

Dr Lewis said that Europe is eyeing many new welfare initiatives. Currently, long-tail production and banning carbon dioxide stunning during slaughter are on the radar as it revises its animal welfare laws with the implementation of the European Green Deal and Farm-to-Fork Strategy. “These new regulations aim to make Europe climate neutral by 2050 and will govern many aspects of modern swine production. The European Food Safety Authority has recommended genetically limiting the number of piglets to between 12 and 14 for breeding purposes, as larger litters result in poorer welfare for the piglet and the sow, as does the use of artificial rearing.”

He said that such legislative changes, should they be implemented, will affect Africa’s pig industry. Therefore, it is essential for the local and regional industry to start thinking about them before they come into practice and perhaps decide if the European model is suitable for African producers.

“South Africa now has a mature genetic and multiplication structure. If the next wave of agricultural development in Africa takes off with the development of farms and investment into north and central Africa, South Africa could become a vital regional genetic hub that’s more affordable than Brazil and North America”.

“I challenge farmers to look down the road as technology rapidly evolves in the coming decade. This is Africa’s opportunity to be proactive, lead the way in terms of new technologies, and drive the future of agricultural production globally.”

This article was published in the spring 2023 issue of PORCUS PrimeCuts.

The South African Pork Producers’ Organisation (SAPPO) coordinates industry interventions and collaboratively manages risks in the value chain to enable the sustainability and profitability of pork producers in South Africa.